Mapping

The project will give researchers and students the opportunity to choose how they would like to engage with the data, either in its raw state, or mapped. It aims to offer the public a unique view on colonial urban slavery and post-slavery society by focusing on one of the Atlantic World’s key commercial centers. By pairing quantitative and visual data, the project presents many new avenues for research that include the real estate heritage of women or free people of color in the town, the spatiality of racial segregation, the polarization of places of trade, and the impact of the Haitian Revolution and fires on the urban, social, and economic landscape of the town.

Insight 1

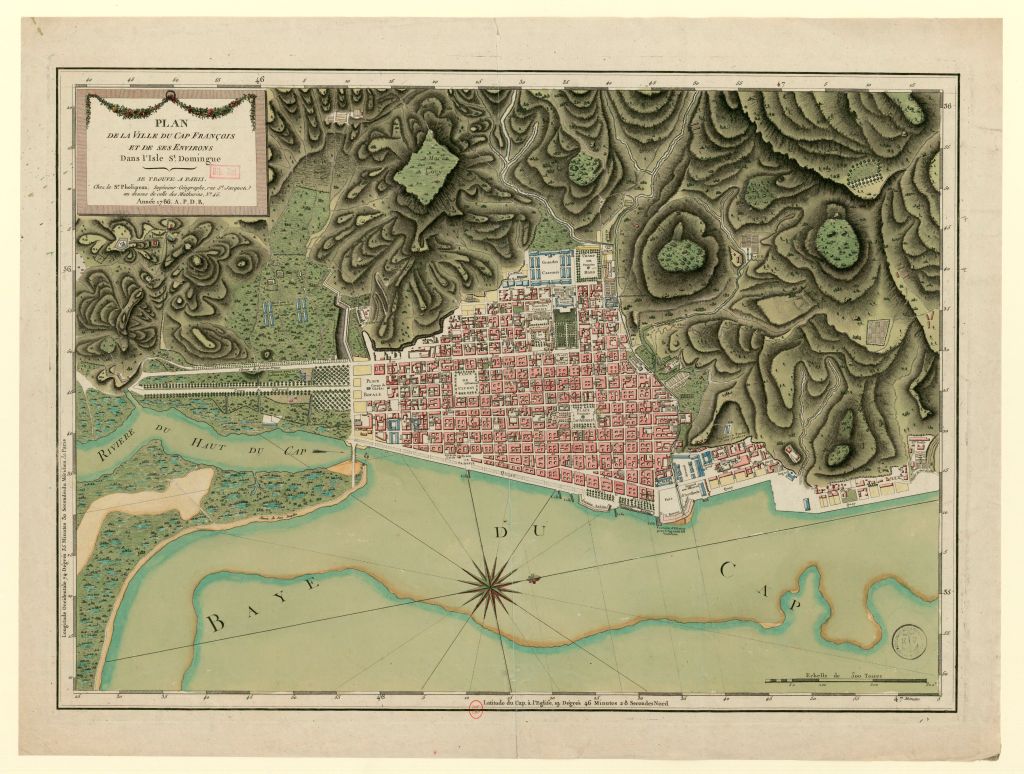

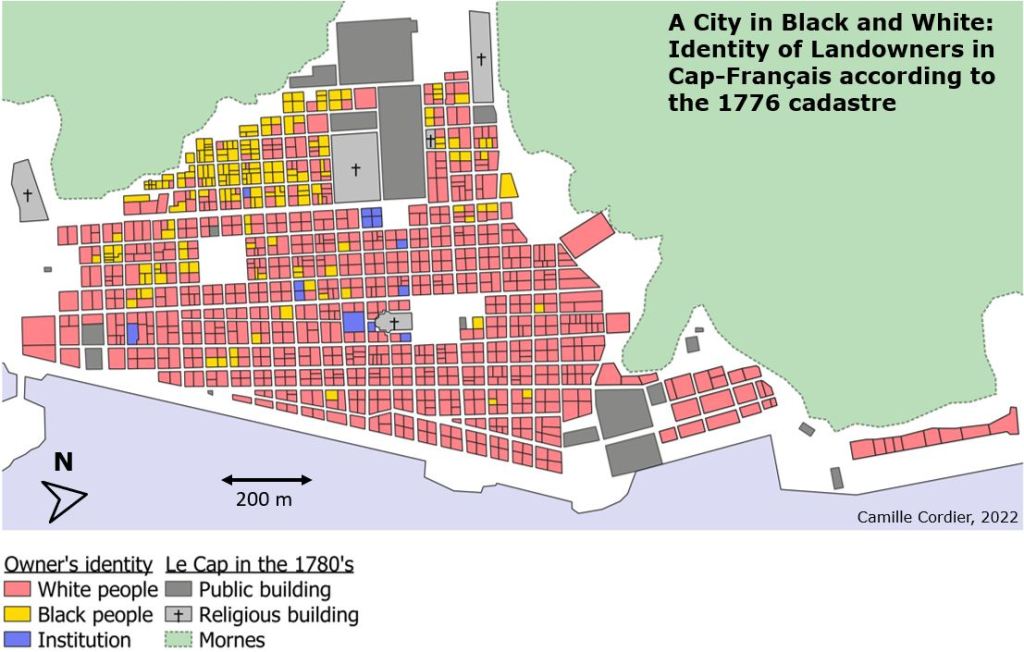

The richness of the project lies in the possibilities of multi-scalar analysis. At the city level, maps will reveal new insights about the social, economic, and physical landscape of the city and its evolution over time. Take this map [Map 1] of the cadastre of 1776, for instance, which outlines the sex and race of the owners of each parcel. Notice the strong contrasts between the districts of the town. Free people of color mostly lived in the Petite-Guinée district (so-called because it was mainly inhabited by the town’s Black residents), while white residents monopolized the seaside.

Insight 2

Indeed, we find additional contrasts on Map 2 representing the estimated value of each plot in the city in 1776. The area between the church square and the quays appears the lucrative district of the town. This is echoed in surviving documents of the time. This was the commercial district where the merchants and the shops of the captains were located. On the contrary, the value of land in the Petite-Guinée district is the lowest.

To better understand this map, we require additional information. And herein lies one of the main objectives of our project—to give researchers the possibility of cross-referencing the data themselves to carry out their own research and analysis.

Our project also allows for a micro-historical analysis of social interactions in public spaces or inside the home and sheds light on the daily lives of city dwellers, free and unfree. At the level of the neighborhood, in the north of the Petite Guinée neighborhood, we can observe that Black and white inhabitants resided on the same block. Gouffre, a Black woman who owned her house, lived near Catherine, a free woman of color, as well as Dame Jalon, a married white woman [Map 3].

We hope that scholars will use the data from In the Streets of Le Cap to cross-reference it with other digital history sources and projects. Take Le Cap resident Joseph Dietrich, who in 1776 resided on rue Espagnole, a street which connected the town to the rest of the colony [Map 4].

Further details about Dietrich’s home may be found by consulting marronnage.info, a site that brings together the maronnage announcements that appeared in French Atlantic newspapers. From this project, we discover that Dietrich’s house was an inn run by Joseph Dietrich himself. Further, Dietrich was a blind white man who owned several slaves. At the same time, we learn that one of them, Thérèse, a 25-year-old Creole, had run away three times in less than two years. Thérèse labored as a peddler and shoe seller outside of the inn, which gave her great freedom of movement. Thus, although the cadastres only name free people, they also allow, with a little imagination and assistance from other digital humanities projects, to retrace the experience of enslaved populations in the urban setting.

Far from being a simple agglomeration of soulless plots, this project will, we hope, be the canvas for future narratives written by historians around the world who share an interest in the history of Saint Domingue, colonial cities, and of the Haitian Revolution.